Grant Broadens Work on Improving Brain-Injury Word Deficits

By: Stephen Fontenot | Sept. 24, 2021

Neuroscientists at The University of Texas at Dallas have received a $2 million Department of Defense grant to expand research into a potential noninvasive, nonpharmacological treatment they designed to help people who have experienced traumatic brain injury (TBI) recover their ability to retrieve words.

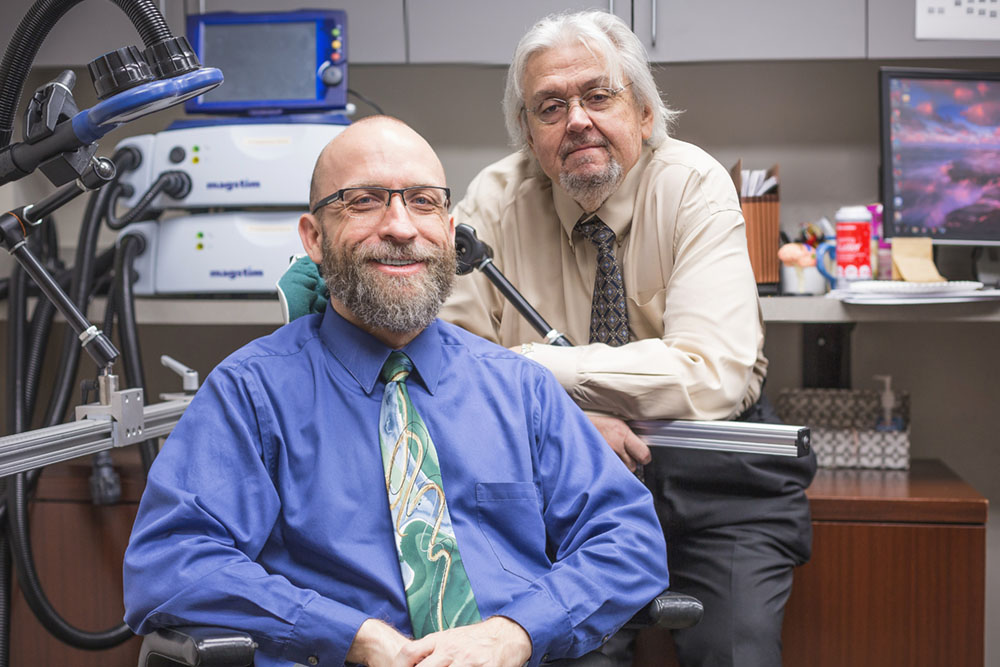

In previously published research, the team, led by Dr. John Hart Jr., the Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, has used functional MRI and EEG to document patterns of brain activity important for verbal retrieval and to identify abnormal activity patterns in TBI patients with word-retrieval issues.

The new method uses high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (HD-tDCS) to deliver low levels of electrical stimulation via electrodes in a cap placed on a person’s head.

“We stimulate specific areas of the brain with a very low level of electrical current,” Hart said. “Subjects barely feel it at all, and there are essentially no side effects.”

“This method was shown in our last paper to help TBI patients who were veterans retrieve words with an effect lasting eight weeks out from treatment.”

Dr. John Hart Jr., the Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences

TBI affects more than 2 million people annually, and it is often brought on by falls, collisions or car accidents. People who suffer mild TBIs, generally classified as concussions, often report difficulty coming up with words, which hinders their ability to converse or convey information.

Hart said that there is currently no Food and Drug Administration-approved intervention for a cognitive difficulty of this nature in TBI patients.

“People try different approaches, but there is no successful, long-lasting treatment for this problem,” he said. “We’re trying a novel, potential treatment, and the downsides are minimal.”

The clinical trial will build on the results of a pilot study published in late 2019 in the Journal of Neurotrauma, for which Hart was corresponding author and Dr. Michael Motes, a senior research scientist at UT Dallas, was lead author.

Clinical Study

To learn more about participating in the high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation study, visit the clinical trials website.

“This method was shown in our last paper to help TBI patients who were veterans retrieve words with an effect lasting eight weeks out from treatment,” Hart said.

Motes added: “The previous paper showed efficacy for the method but was preliminary in terms of having a small pool of subjects and limited assessments. The new study will have two parts. First, we’ll see if we get this effect in a larger group of subjects, as well as some of the broader effects that the first study hinted at. We’re also hoping to learn what kind of patient is a prime candidate and what is the optimal number of sessions.”

Scientists plan to administer 15 sessions of HD-tDCS to between 40 and 80 participants, some of whom will receive a “sham” treatment as part of the triple-blind study. All participants will be tested on verbal retrieval several times over a three-month period after the final treatment.

Both scientists emphasized that, in addition to having few potential side effects, the treatment’s advantages over drug-based therapies also include the degree to which the method is focused on a specific area of the brain.

“Even if there is someday an approved pharmacological intervention for this type of problem, it wouldn’t be targeted to any single region of the brain,” Motes said. “In general, treating TBIs has not often been focused to a single specific cognitive deficit.”

“The new study will have two parts. First, we’ll see if we get this effect in a larger group of subjects, as well as some of the broader effects that the first study hinted at. We’re also hoping to learn what kind of patient is a prime candidate and what is the optimal number of sessions.”

Dr. Michael Motes, senior research scientist at UT Dallas

Hart said a pharmaceutical treatment would blanket every area of the brain, which would result in a greater likelihood of side effects.

“While you’re trying to regulate a lagging area, you might also disrupt an area that’s healthy. Instead, our method targets the memory sites that we’ve determined are most likely affecting the word-retrieval problem,” he said.

Before HD-tDCS intervention begins, participants will be assessed on finding words, naming objects and memorizing lists. They will also undergo EEG scans of both resting brain activity and activity associated with selecting named objects.

“Simply put, we’re targeting an area of the brain that seems dysfunctional,” Hart said. “We’re treating the symptoms — things that make it hard for people to work or go to school. There have been no other real treatment options, and we’re offering something quite safe.”

Researchers hope to firmly establish that HD-tDCS for verbal retrieval deficits can significantly improve not only performance on neuropsychological tests, but also day-to-day functions, such as the fluent conversation skills that underpin social and work interactions. Because the technology used is relatively inexpensive and easy to use, the researchers believe the treatment could be made widely available at medical centers.

“If this method continues to be effective, I think the future of this technology could be simply writing electrical prescriptions of dosage and region of the brain, based on the nature of the deficit,” Hart said. “But we still have a lot of work to do.”

Media Contact:

Stephen Fontenot, UT Dallas, 972-883-4405, stephen.fontenot@utdallas.edu, or the Office of Media Relations, UT Dallas, (972) 883-2155, newscenter@utdallas.edu.