Brain Imaging Links Cardiovascular Health to Multitasking Ability

By: Stephen Fontenot | Oct. 30, 2020

Adults over 60 with optimal blood pressure and high fitness levels can keep up mentally with people half their age, according to a recent brain-imaging study from researchers in The University of Texas at Dallas’ Center for Vital Longevity (CVL).

Dr. Chandramallika Basak, associate professor in the Department of Psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences and director of the CVL Lifespan Neuroscience and Cognition Laboratory, said the findings help define the characteristics of “superagers” and shed light on the clearest path to late-life cognitive health.

Basak is senior author of a study published Sept. 9 in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience that uses functional MRI (fMRI) to investigate the effects of low fitness levels and hardened arterial walls on brain activations during a task-switching exercise. The results suggest that these cardiovascular risk factors act independently in hampering the performance of the aging mind. For people with both risk factors, the detrimental effects on the aging brain is compounded.

“This kind of research helps us understand how various health factors can help protect us against declines in cognition by promoting brain activation,” Basak said. “Only with that understanding can we begin to think about effective interventions in mid- and late life.”

“You might believe that if you stay fit, it will help maintain your blood pressure, and that in turn should prevent hardened arteries. But we are learning that these operate independently — that fitness doesn’t cut out all of the cardiovascular risk on brain functions.”

Dr. Chandramallika Basak, director of the Lifespan Neuroscience and Cognition Laboratory at the Center for Vital Longevity

For the study, pulse pressure calculated from blood pressure levels was used to measure arterial hardness, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Basak said that most cognitive researchers have studied the effects of either fitness level or blood pressure level in the belief that the factors are correlated and represented essentially the same measure of cardiovascular health.

“You might believe that if you stay fit, it will help maintain your blood pressure, and that in turn should prevent hardened arteries,” she said. “But we are learning that these operate independently — that fitness doesn’t cut out all of the cardiovascular risk on brain functions.”

CVL research associate Shuo (Eva) Qin PhD’19, the lead author of the paper, described another surprise: Older participants with no risk factors performed as well as younger adults.

“There is no statistically significant difference between younger adults and high-health older adults in brain activations,” she said. “We expected a small gap, but not no gap at all.”

The 88 participants included 60 in a 60-or-older cohort and 28 in a control group of UT Dallas students ages 18 to 30. No one in the older group had extraordinarily low or high fitness levels, or suffered from uncontrolled hypertension.

“Even within this restricted group of healthy adults, if you have greater arterial stiffness or lower general fitness — or worse, both — it depletes your neural resources and your cognitive performance is significantly worse,” Basak said.

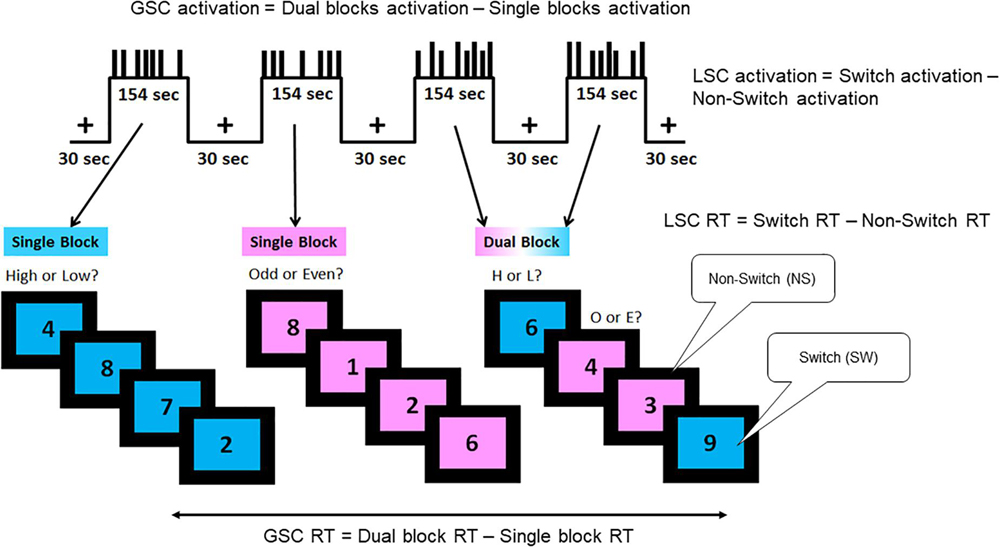

For the cognitive task, participants viewed a single-digit number on either a pink or blue background. If the background was blue, subjects had to indicate if the number was high or low; if it was pink, they had to determine if the number was odd or even. Participants initially did the tasks separately, then the tasks were randomly interspersed.

“We chose numbers because they are not biased against old age, native language, gender, race or socioeconomic status,” Basak said. “The timing in the task is also random so participants’ brains can’t get into a rhythm and plan in advance the timing of when the numbers appear.”

Qin said that the task-switching paradigm used in the study measures various cognitive processes, including some that are not affected by aging.

“This allows us to examine effects of cardiovascular health factors on brain activations that are either affected by age or not affected by age,” she said. “Such a multidimensional approach can investigate effects of cardiovascular health factors on brain functions beyond general aging.”

In fMRI, the brain is scanned about every second as the participant performs a mental task. Since more active brain areas use more oxygen, researchers can distinguish brain regions that activate during the task by an increase in flow of oxygenated blood to that region. One well-established pattern found in fMRI results of aging brains is that older adults activate frontal regions in addition to posterior regions while doing a memory or multitasking or visual task, while younger adults require only the posterior regions, where visual tasks normally take place.

“What we found in our study is that older adults activate these posterior regions about the same as younger adults,” Basak said. “But low-fitness older adults are also activating additional frontal regions in an attempt to maintain their performance. But this compensation effort is maladaptive; it doesn’t succeed in restoring their performance levels.”

At the Speed of Bright

UT Dallas has earned a reputation for incredibly bright students, innovative programs, renowned faculty, dedicated staff, engaged alumni and research that matters. Read stories about more of the University’s bright stars.

The researchers found that low-fitness older adults are specifically activating the inferior frontal gyrus — part of the prefrontal cortex — when they have to do two tasks simultaneously.

“When the task is simple, the fMRIs of low-fitness older adults look very similar to the high-fit and young,” Basak said. “The difference is only apparent in the low-fitness brains when the tasks get harder. And the more you activate this region of the brain, the worse your performance is.”

While the brain images don’t conclusively indicate that cardiovascular risk factors cause cognitive issues, they do strongly suggest the two are related.

“There are cardiovascular-related differences in brain activation, and the greater your risk factors, the worse you perform,” Basak said. “That doesn’t establish cause and effect; to do that is impractical.”

As the connection between these risk factors and cognitive decline become more firmly established and the characteristics of superagers are refined, Basak hopes

that tactics for maintaining cognitive function can become widespread.

“We hope to find ways to create superagers via interventions later in life in order to help with cognitive problems relating to fitness or blood pressure,” she said.

This research was partially supported by National Institute on Aging grant R56AG060052 as well as a grant from the Advanced Imaging Research Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Media Contact: Stephen Fontenot, UT Dallas, 972-883-4405, stephen.fontenot@utdallas.edu, or the Office of Media Relations, UT Dallas, (972) 883-2155, newscenter@utdallas.edu.