Nobel Laureate To Recall Work with Renowned UT Dallas Physicist at Lecture

By: Amanda Siegfried | Aug. 25, 2021

Nobel laureate Sir Roger Penrose, the British mathematical physicist who in the 1960s formulated many of the basic features of black holes, will give a virtual public lecture to The University of Texas at Dallas community at noon Thursday, Sept. 2, in honor of his friend and collaborator Dr. Wolfgang Rindler.

The lecture, hosted by the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and available via Zoom, is titled “Spinors, Space-Time, and Working with Wolfgang Rindler.”

In 1963 Rindler was one of the founding faculty members of the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest, which became UT Dallas in 1969. A dedicated and highly praised teacher, he was instrumental not only in the establishment of the Department of Physics, but also in the rise of scientific research at the University. In a career that spanned more than 60 years, Rindler was one of the most prominent experts in theoretical relativistic cosmology and general relativity, areas of research that deal with the origin, evolution and structure of the universe. He died in 2019.

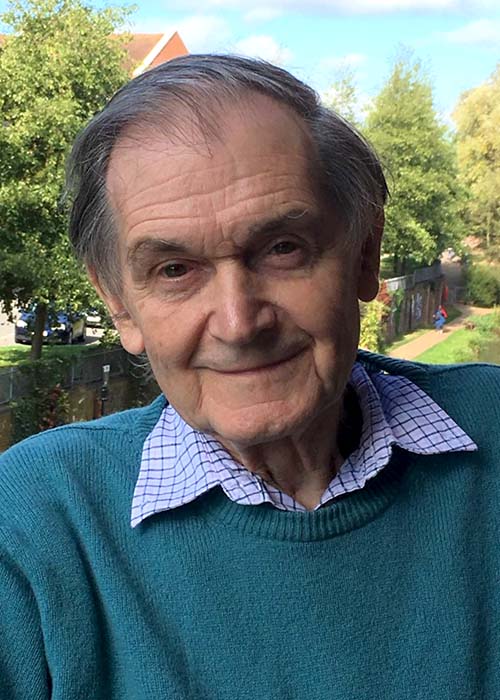

Penrose is the Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford and an emeritus fellow of Wadham College at Oxford. He is a fellow of The Royal Society, an international member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and a recipient of numerous awards, including the 1988 Wolf Foundation Prize in Physics, which he shared with Dr. Stephen Hawking.

Penrose was the co-winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize in physics for his discovery that black holes are a direct consequence of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which describes gravity. Black holes are supermassive but compact regions in space where space and time are distorted and gravity is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape.

In his talk, Penrose will discuss his 25-year collaboration with UT Dallas’ Rindler and what was distinctive about the techniques they developed in advancing the understanding of Einstein’s theory. Their relationship began in the early 1960s, when the two shared an office at King’s College London.

“I had, some time earlier, been developing a certain family of mathematical techniques for the study of Einstein’s general theory of relativity using what are called two-component spinors,” Penrose said. “The techniques of using spinors in general relativity were somewhat unusual, as spinors had been used in physics primarily for the study of quantum mechanical spin of particles and not for general relativity theory. However, I had found that two-component spinors could be enormously useful in relativity theory if used in the right way, and I gave a lecture on this while at King’s College.

“Wolfgang found this useful, and potentially important, and we started collaborating on a work intended to spread these ideas more widely. This started in the form of mimeographed notes, but soon we got very involved in the work and contacted the Cambridge University Press to find out if they would take on the project — which they subsequently did. There is no really comparable work on this subject, developed to the degree that we were able.”

In the 1980s the co-authors published their work in a seminal two-volume textbook, Spinors and Space-Time. They described spinors, which are complex mathematical objects that don’t come back to themselves under 360-degree rotation, but do upon 720 degrees of rotation. Spinors help describe the behavior of ordinary matter and are used to model a range of problems in theoretical physics, including relativity and space-time.

“I very much enjoyed working with Wolfgang,” Penrose said. “I recall that he had a particular skill. I would write some concept or technique in some rather obscure way, and Wolfgang would then ‘Rindlerize’ it, as he would say, putting it in crystal-clear, simple language. Sometimes we were able to work together in the same location; at others we had to communicate at a great distance, by post. For me it was a truly unforgettable and deeply personal illuminating experience.”

Dr. Anvar Zakhidov, professor of physics at UT Dallas who was involved in arranging Penrose’s lecture, said he first learned about the collaboration between the pair in the 1980s in Moscow when he was trying to learn spinor physics and read their book, which had been translated into Russian.

“I very much enjoyed working with Wolfgang. I recall that he had a particular skill. I would write some concept or technique in some rather obscure way, and Wolfgang would then ‘Rindlerize’ it. … For me it was a truly unforgettable and deeply personal illuminating experience.”

Sir Roger Penrose

“I never imagined then that I would become Wolfgang’s friend and colleague at UT Dallas for nearly 20 years,” Zakhidov said. “That scientific collaboration of two giants changed our current vision of the universe and its most unusual objects: black holes. It is amazing that black holes so elegantly justified by Penrose’s mathematics at extreme gravitation can also be independently described by the ‘Rindler Horizon’ concept at extreme acceleration.”

At Rindler’s invitation, Penrose visited the UT Dallas campus in 2006 to give a public seminar and was on campus again in 2013 for the 50th anniversary of the Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics.

“Among his many admirable traits, as a professor and person Wolfgang exemplified the love of learning, a sense of wonder and an almost boundless capacity for friendship,” said Dr. Dennis Kratz, senior associate provost, director of the Center for Asian Studies and the Ignacy and Celina Rockover Professor of Humanities. “What a perfect way to begin this academic year — with a lecture honoring him by a friend who is a Nobel laureate and a leading cultural icon.”

Media Contact:

Amanda Siegfried, UT Dallas, 972-883-4335, amanda.siegfried@utdallas.edu, or the Office of Media Relations, UT Dallas, (972) 883-2155, newscenter@utdallas.edu.