New Research Center Focuses on Semiconductor Security

By: Kim Horner | July 16, 2021

Just as computer networks can be susceptible to cyberattacks, semiconductor chips also can be vulnerable to tampering in ways that could compromise the safety of cars, airplanes, electric grids, defense systems — any of the growing number of technologies that depend on these tiny electronic components.

To address this risk, The University of Texas at Dallas, along with five other universities, has established the Center for Hardware and Embedded Systems Security and Trust (CHEST), a new research center focused on protecting the security of semiconductors, the circuit boards they are mounted on and other computer hardware. Led by the University of Cincinnati, CHEST also involves Northeastern University; University of California, Davis; University of Connecticut; and the University of Virginia.

CHEST is a National Science Foundation (NSF) Industry-University Cooperative Research Center (IUCRC) that serves as a hub for industry-focused research and currently comprises 23 members across industry and governmental laboratories.

Dr. Yiorgos Makris, professor of electrical and computer engineering in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science, received a $750,000, five-year NSF grant in 2019 to launch the UT Dallas CHEST site, which opened in 2020. The center also provides opportunities for University faculty and students to conduct research for other federal agencies. So far, UT Dallas researchers have received $705,000 for research projects in the first two years.

“Increasingly, hardware can be the entry point for a cyberattack,” said Makris, who directs the UT Dallas CHEST effort. “That’s why it is so important for researchers, industry, and national and federal laboratories to work together to develop solutions. We are excited to be part of such a collaborative effort through CHEST.”

The overall investment in CHEST exceeds $13 million, including equal NSF funds for each university and dues from Industrial Advisory Board members. Congress included $3 million for the center through the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act.

UT Dallas leads the consortium’s research on the security and trust of wireless communication devices, threat detection and prevention, protection of intellectual property from unauthorized use, and provenance attestation, which involves a record that describes entities and processes involved in producing the devices.

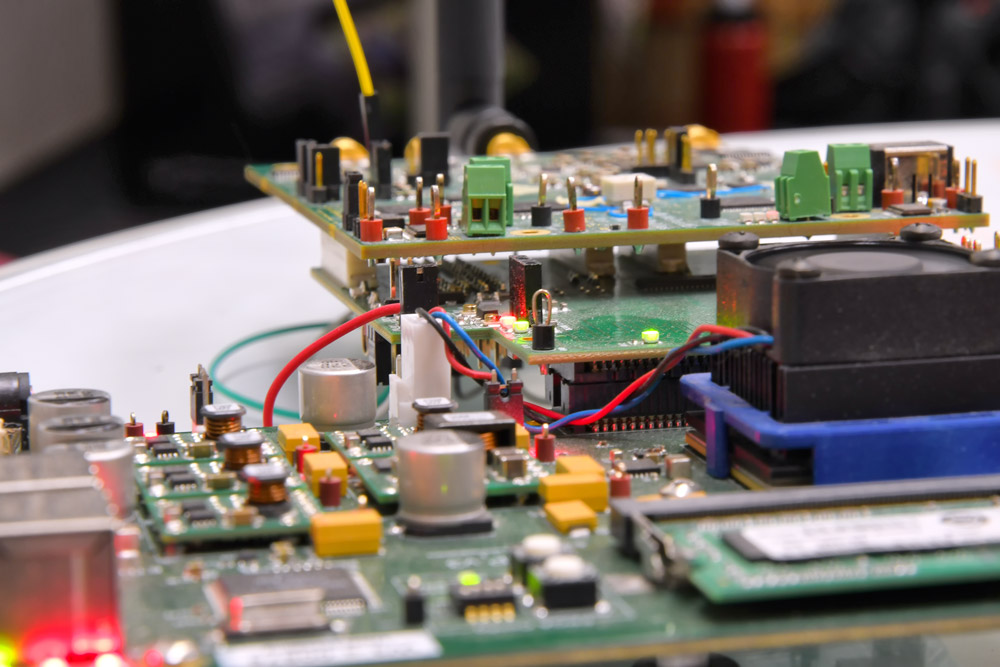

Semiconductor chips — often referred to as simply semiconductors — make it possible for electronic devices to process, store and transmit data. Most semiconductors are composed of sets of integrated electronic circuits layered on a thin wafer of semiconductor material in an area as small as a few square millimeters.

“Increasingly, hardware can be the entry point for a cyberattack. That’s why it is so important for researchers, industry, and national and federal laboratories to work together to develop solutions. We are excited to be part of such a collaborative effort through CHEST.”

Dr. Yiorgos Makris, professor of electrical and computer engineering in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science

As the use of electronic devices grows, their components have become increasingly vulnerable to malicious tampering and counterfeiting. As an example, Makris described a scenario of how tampering could affect the electronics that control critical infrastructure such as the power grid.

“Suppose a bad actor replaces a chip during a service or upgrade, enabling capabilities that can cause the power distribution network to fail,” Makris said. “Semiconductor tampering also has implications for consumer electronics, such as wireless communication devices, where private data may be leaked by untrusted chips, or the automotive industry, where safety may be compromised by counterfeit parts.”

The global shortage of semiconductors increases the risk of the use of counterfeit parts, Makris said.

“The semiconductor shortage does not just affect productivity and the ability of industry to keep producing cars, phones and consumer electronics,” he said. “The situation also has deeper security implications as desperate suppliers or consumers turn to the gray market to find parts.”

While the U.S. is a leader in semiconductor design, most of the manufacturing has shifted progressively out of the country over the past 30 years, leaving the U.S. vulnerable to supply chain disruptions out of its control, according to an April 2021 study by the Semiconductor Industry Association. The U.S. Senate recently approved legislation called the United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021, which in part would provide $52 billion to incentivize domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

Companies that design the chips potentially can lose control of what happens to their intellectual property during the manufacturing process, Makris said.

“You don’t want an adversary to get access to the chip blueprint,” Makris said. “Otherwise, you may lose control of your competitive edge.”

Makris joined UT Dallas in 2011 after more than 10 years as a faculty member at Yale University. To help ensure the trustworthiness of chips, Makris and his research group have pioneered techniques that use machine learning and statistical and formal methods to discover malicious capabilities, detect counterfeits and attest the facility wherein chips were manufactured.

In addition to his role as CHEST site director, Makris leads the safety, security and health care thrust of the Texas Analog Center of Excellence and is director of the Trusted and RELiable Architectures Research laboratory, both at UT Dallas.

Media Contact:

Kim Horner, UT Dallas, 972-883-4463, kim.horner@utdallas.edu, or the Office of Media Relations, UT Dallas, (972) 883-2155, newscenter@utdallas.edu.