Understanding the psychological mechanisms and motivations that lead some older adults to make riskier financial decisions than younger adults underlies a University of Texas at Dallas researcher’s new investigations, funded by a $560,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

“I’m interested in the shifts that happen in terms of motivation and how that influences decision-making,” said Dr. Kendra Seaman, assistant professor of psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. “We hope to understand which older adults are most vulnerable to making poor decisions, why they are more vulnerable, and how we can intervene to help them make better decisions and improve their lives.”

For instance, each year more than 5% of older Americans are victims of financial fraud, according to a 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health. Estimates of annual losses from elder fraud may be as high as $36 billion.

“When there’s a really small chance of something big happening, like winning the lottery, people in general are drawn in — and older adults even more so. My research is trying to figure out why that’s the case.”

Dr. Kendra Seaman, assistant professor of psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences

The reasons why older adults might make poor decisions compared with younger adults are often attributed to age-related cognitive decline or misunderstanding of technology. Seaman, who is also the principal investigator for the Aging Well Lab in UT Dallas’ Center for Vital Longevity, suspects that changes in decision-making capabilities over time also reflect evolving priorities of older adults based on their life experiences.

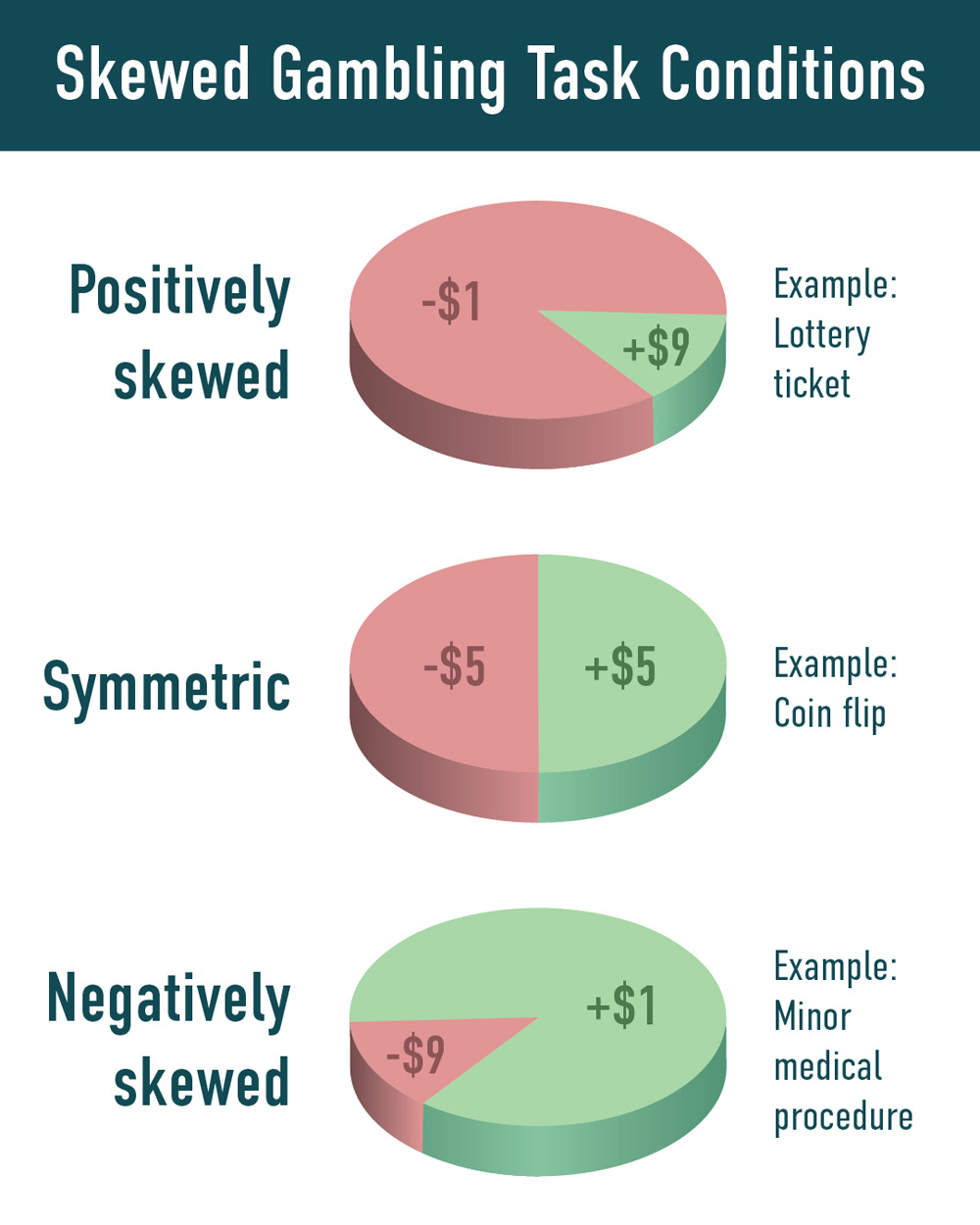

One situation in which older adults seem more susceptible to financial fraud involves positively skewed risks: decisions involving options that juxtapose large but unlikely gains against small, likely losses. This is a scenario presented by many financial scams.

“When there’s a really small chance of something big happening, like winning the lottery, people in general are drawn in — and older adults even more so,” she said. “My research is trying to figure out why that’s the case.”

To explain the discrepancy, Seaman set out a simple wagering example of three situations where the values of participating are mathematically equal: one with a 75% chance of losing $1 and a 25% chance of winning $3; another with 25% chance of losing $3 and a 75% chance of winning $1; and a third with a 50% chance of either winning $2 or losing $2.

“Theoretically, people should accept each of these gambles equally often. But that is not what happens,” she said. “People accept positively skewed gambles — the low-chance, high-reward scenario [the first scenario] — more often than symmetric or negatively skewed gambles. This is called the positive-skew bias: People like positively skewed gambles more than other equivalent ones. This bias is what we would ultimately like to reduce.”

Seaman and her collaborators are designing experiments around the hypothesis that older adults’ positive-skew bias is driven by separate but related factors, including an increased focus on upsides.

“One theory behind this is called ‘positivity effect’ in aging, which asserts that older adults tend to be drawn to positive information and remember it better than neutral or negative information,” Seaman said. An example is remembering someone smiling rather than frowning.

Seaman’s behavioral studies will involve healthy adults ages 25 to 85. The first set of experiments, concerning positivity effect, will ask participants about the details of a series of financial decisions as they make them.

“We’ll test their memory for what they just did by asking how much they could have potentially won with their decision,” Seaman said. “For the attention component, we’ll employ an eye tracker, which uses infrared to figure out where a person is looking on the screen and for how long. Existing research suggests that this is predictive of the choice that they make.”

Separately, the team will also test the effect of cognitive control, which researchers believe allows older adults to avoid potential losses.

“Our tests will have participants busy doing other memory tasks, or we will put them under time pressure, which will impair their cognitive control. We want to see how that affects their decisions,” Seaman said.

How To Participate

The Aging Well Lab is currently recruiting subjects for several studies. To inquire about participating, send an email to AgingWellLab@utdallas.edu.

To learn more about how UT Dallas is enhancing lives through transformative research, explore New Dimensions: The Campaign for UT Dallas.

A previous neuroimaging study by Seaman found both that older adults were drawn to positively skewed gambles more than younger adults, and that older adults were activating regions of the brain associated with cognitive control while looking at gambles with a large chance of a small loss.

“We’re trying to see if that correlation is actually causation,” she said.

The risks presented in the study all are financial because that makes for easily quantifiable variables that are also easily modulated.

“It allows us to manipulate the amount of reward and see how that impacts decisions,” Seaman said. “Older studies have looked at hypothetical social and health rewards, but quantifying those is problematic. Instead, we will focus on money, even though some studies have shown that older adults seem to value money less than other factors, like social ties and emotional stability.”

Weighing the impact of evolving outlooks against the influence of any kind of cognitive decline is the principal challenge of this type of study.

“How much of decision-making is due to either motivational changes or changes in context, compared to any kind of impairment? The problem is, it’s all of those things,” Seaman said. “Research exists suggesting that impaired financial decision-making is an early predictor of Alzheimer’s disease. But there are also people for whom motivational shifts are the driving factor. We’re still trying to figure out how much of it is each different component, as well as potentially other components we haven’t identified yet.”